I have no doubt. And even though he didn’t live to see his own 36th birthday he left a recorded legacy of hundreds of recordings, most still unsurpassed by any other tenor since.

I have no doubt. And even though he didn’t live to see his own 36th birthday he left a recorded legacy of hundreds of recordings, most still unsurpassed by any other tenor since.

His name is Fritz Wunderlich. He was the reason I became hooked on opera at the age if 11, and I have spent countless hours listening to his recordings again and again. Recordings that span a period of only a rough decade, terminating in 1966.

On September 5th that year Fritz Wunderlich appeared at the Edinburgh Festival in a performance of Die Zauberflöte, and once more he was hailed as the outstanding Mozart tenor of the day. Wunderlich had sung Tamino hundreds of times before, but after the Edinburgh performances he asked Ferdinand Leitner, who was conducting, to go through the score with him. Wunderlich was not satisfied with his Tamino anymore – he knew that he could do better, and he wanted to bring new life to his interpretation. Leitner agreed to help, and invited him to his house. A date was settled for; Sunday September 18th.

Fritz Wunderlich never met Leitner that Sunday. Wunderlich died tragically the day before after falling down the stairs in a friend’s hunting lodge. The banister made of rope was not securely fastened to the wall and when Wunderlich tripped on the staircase he tore it out, falling head first onto the stone floor below. Afterwards it was noticed that Wunderlich had forgotten to tighten one of his shoe laces. He was taken unconscious to hospital, where he died a few hours later – little more than a week before his 36th birthday. The Edinburgh Zauberflöte was his last appearance on stage.

One of the most remarkable tenors in recording history was granted a career of only slightly more than a decade. All the more remarkable is the amazing number of recordings he made, many of which have remained in the catalogue continually to this date. Even in his very first sessions we hear some of the qualities that made Wunderlich the most celebrated German tenor after the War: The natural freshness of his voice, the expressive musicality, and above all his boundless enthusiasm. Wunderlich always sounds as if he is completely convinced of the music he is singing, be it Wozzeck or Der Bettelstudent.

Friedrich Karl Otto Wunderlich was born on September 26th, 1930 in the small village of Kusel in south-western Germany, close to the French border. Besides running a local inn with a small movie theatre both his parents were part-time musicians, and before his teens Fritz learned to play both the accordion and the trumpet. He often played dance music in his youth, and sometimes he would also croon a refrain. His voice turned out to be a natural tenor, and at the age of 19 he took his first singing lessons from a professional coach; once a week Wunderlich would bike the 40 kilometres to Kaiserslautern – and back again.

Friedrich Karl Otto Wunderlich was born on September 26th, 1930 in the small village of Kusel in south-western Germany, close to the French border. Besides running a local inn with a small movie theatre both his parents were part-time musicians, and before his teens Fritz learned to play both the accordion and the trumpet. He often played dance music in his youth, and sometimes he would also croon a refrain. His voice turned out to be a natural tenor, and at the age of 19 he took his first singing lessons from a professional coach; once a week Wunderlich would bike the 40 kilometres to Kaiserslautern – and back again.

In 1950 he was accepted at the Hochschule für Musik in Freiburg, where he studied with Margarethe von Winterfeld. She taught him the technical basis of singing, devoting much time to intonation and breathing. Wunderlich made progress, and in 1954 he was chosen as Tamino in the Hochschule’s staging of Die Zauberflöte. He was now on his way towards a career that would soon give him his first contract with an opera house; a five-year beginner’s contract with the Württemberg State Opera in Stuttgart. Again, his first major role was Tamino. On February 18th, 1955 Wunderlich stepped in for an indisposed Josef Traxel, and was immediately recognised by both the audience and the critics as the new young lyric tenor of the theatre.

Others had their eyes and ears on Wunderlich too. Until recently it was believed that Wunderlich’s first experience in a recording studio was in late July 1955, recording Monteverdi’s Orfeo with August Wenzinger for Deutsche Grammophon’s Archiv label, but now it has been determined that Wunderlich’s recording debut took place a few days before in Stuttgart on July 17th, when the 24-year old singer recorded the tenor solo in Beethoven’s Symphony no. 9 with the Stuttgart Philharmonic conducted by Isaie Diesenhaus. Later in 1955 Wunderlich recorded, also in Stuttgart, a Bach cantata with the conductor Marcel Couraud for the French label Les Discophiles Francais.

Soon after Wunderlich was contacted by the Stuttgart-based record club Europäische Phonoklub. They wanted him as an exclusive artist, and the newly-wed Wunderlich was only happy to accept a monthly fee for a fixed number of recordings each year – a well needed supplement to his salary at the Stuttgart Opera. The Phonoklub recordings were intended for sale through the club only, and were not distributed to regular shops. The masters, however, were later bought by Eurodisc, who did not hesitate to issue them on a broader scale – much to the annoyance of Wunderlich, who tried persistently but fruitlessly to prevent the reissue of this material.

The first session for Europäische Phonoklub took place in September 1956. Wunderlich was to record highlights from La Bohème, Rodolfo being a part he had not studied in any detail. He turned up to the session at the Hotel Esplanade having prepared the first act aria and the following duet with Mimi only, and much to his surprise learned that he was also required to sing several ensembles scheduled for recording that same day. Fortunately, Wunderlich was phenomenal at sight-reading, thanks to his early experiences playing dance music, and indeed many of the popular songs and operetta arias Wunderlich later recorded were items that he saw more or less for the first time at the recording sessions.

During the following four years Wunderlich recorded extensively for EPK, mostly highlights from popular operas and operettas such as Cavalleria Rusticana, Madame Butterfly, Die Fledermaus and Raymond’s Maske in Blau, as well as several 7 and 10 inch records mainly consisting of single opera and operetta arias, all sung in German. The original Europäische Phonoklub records are not easy to find on the second hand market today, but a small selection from these recordings are now available on CD.

In 1956 Les Discophiles Francais again approached Wunderlich regarding a recording of three further Bach cantatas. Wunderlich, being tied to his contract with EPK, solved the problem; he used the assumed name of Werner S. Braun for the recordings, pressed in only 200 copies each, and numbered by hand in Roman numerals. When Philips later reissued the cantatas Wunderlich was still listed as Werner S. Braun on the cover.

Wunderlich was a frequent guest in the studios of the German radio stations, and a still increasing number of live recordings and broadcast productions of repertoire Wunderlich never recorded commercially are becoming available from companies such as Orfeo, Bella Voce and Myto. One of the most outstanding is the 1959 Salzburg recording of Richard Strauss’ Die schweigsame Frau. The part of Henry Morosus was Wunderlich’s debut at the Salzburg Festival, and the cast included Hans Hotter and Hermann Prey, the latter to become one of Wunderlich’s closest friends. Karl Böhm conducted the performances, and after the first performance Herbert von Karajan came backstage with a contract for the Vienna State Opera. But Wunderlich had to decline; he had just signed up with the opera in Munich, and he was determined to honour his obligations towards this contract.

Wunderlich was a frequent guest in the studios of the German radio stations, and a still increasing number of live recordings and broadcast productions of repertoire Wunderlich never recorded commercially are becoming available from companies such as Orfeo, Bella Voce and Myto. One of the most outstanding is the 1959 Salzburg recording of Richard Strauss’ Die schweigsame Frau. The part of Henry Morosus was Wunderlich’s debut at the Salzburg Festival, and the cast included Hans Hotter and Hermann Prey, the latter to become one of Wunderlich’s closest friends. Karl Böhm conducted the performances, and after the first performance Herbert von Karajan came backstage with a contract for the Vienna State Opera. But Wunderlich had to decline; he had just signed up with the opera in Munich, and he was determined to honour his obligations towards this contract.

In 1959 Wunderlich was offered a new recording contract, this time by Electrola, the German branch of EMI. Now, at the age of 29, he was recording for one of the leading companies. This also meant that he was competing with the other leading tenors on this label, mainly Nicolai Gedda and Rudolf Schock. During his time with Electrola Wunderlich was not allowed to record anything already in the company catalogue featuring other singers. Wunderlich consequently could not record his core repertoire, and this explains the absence of a complete Die Zauberflöte, Don Giovanni or Cosi fan tutte from Wunderlich’s Electrola period. Instead he recorded two German operas in the popular area; Nicolai’s Die lustigen Weiber von Windsor and Lorzing’s Der Wildschütz, two minor Wagnerian roles as well as numerous opera and operetta exerpts. Perhaps the most successful of the Electrola recordings is Smetana’s The Bartered Bride, a recording that reveals Wunderlich’s great comic talent, and shows how much fun and sparkling joy he is able to get across to the listener.

At the other end of the scale a couple of the Electrola recordings never seizes to amaze. Why, for instance, are the accompaniments for the two arias from L’elisir d’amore tampered with both harmonically and regarding the instrumentation? Surely, no one today would dream of exchanging the bassoon in ‘Una furtina lagrima’ with a cor anglaise! Or add a diminished chord and some romantic sounding chromatics to the few bars of the orchestral introduction to ‘Quanto é bella’.

In 1964 Wunderlich signed a new recording contract, this time with Deutsche Grammophon. His career now finally centred around the Vienna State Opera, and Wunderlich was in demand from opera houses all over Europe. Although the had to turn down more than 90 per cent of all the offers he received, a day with a morning rehearsal, an afternoon recording session and an evening performance was not unusual to Wunderlich.

One of the first recording projects for Wunderlich under his new contract was a very special event. His legendary Tamino was to be recorded in Berlin in June 1964, with Karl Böhm conducting, and among his partners were Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, Roberta Peters, Franz Crass, Evelyn Lear and Hans Hotter, in a set that is still one of the great Mozart recordings of all time. It is interesting to compare Wunderlich’s three commercial recordings of the ‘Bildnis’ aria from Die Zauberflöte. Going back to the 1958 recording for EPK we hear a nice, youthful voice, but throughout Wunderlich has a tendency to break the legato. He often separates repeated vowels with a ‘ha’ or ‘he’ sound; ‘und ewig wäre Sie dann mein’ becomes ‘un e-he-wi-hig wä-hä-re Sie dann mein’. This, combined with a habit of often starting a note softly and then make a crescendo on it, does not help the legato much.

In his next studio recording of this aria in 1960 with Berislav Klobucar Wunderlich’s voice has matured into the timbre of his peak. He still has not quite got rid of some of his earlier habits, but this is certainly a much more convincing interpretation.

Finally the complete recording from 1964, captivated in superb sound by the DG engineers. This performance has never been equalled on record for beauty, style and elegance. Here we have the ideal Tamino, a part that has matured with countless performances all over Europe with the world’s leading conductors. Just listen to the way Wunderlich builds up to the climax at the end of the aria. A truly great performance, one that I seriously doubt will ever be surpassed.

Besides his opera repertoire Wunderlich throughout his career sang in countless performances of the Bach passions and cantatas, and he was especially praised for his dramatic and yet deeply profound Evangelist in Bach’s Matthäus Passion. Unfortunately Decca for their only Wunderlich recording in 1964 chose to let him sing the arias only, leaving the Evangelist to Peter Pears. But happily Wunderlich’s Evangelist has been preserved in a 1962 live recording from Vienna conducted by Karl Böhm, recently unearthed and issued by Myto. Wunderlich is in superb voice, as is Christa Ludwig, but the set is marred by an inadequate choir and performances by Wilma Lipp and Otto Wiener that were better kept in eternal darkness. Listen with your finger on the CD-player’s skip button!

In November 1964 Wunderlich was in London for the only EMI recording still to come – one that goes right to the top of my desert island list; Mahler’s Das Lied von der Erde with Otto Klemperer conducting. Often sung by strained and stiff heldentenors, it is a relief to hear the three songs with the perfect mixture of a forward, beautifully lyric sound combined with a powerful, flexible and full scaled interpretation. Wunderlich is in complete control of the dynamic demands made by Mahler ranging from the electrifying vision of the howling ape in the first song to the solemn description of the little pond with the green pavilion made of porcelain in the third.

The following year Wunderlich recorded the part of Andres in Alban Berg’s Wozzeck with Karl Böhm conducting. Wunderlich not only sang the fiendishly difficult music with complete ease, but also contributed the whistling required by Andres in the score, normally done by one of the flautists in the orchestra. Later that year he recorded Bach’s Weinachts Oratorium with Karl Richter in Munich, as well as another Mozart opera, Die Entführung with Eugen Jochum conducting. Here Wunderlich includes a glorious account of the virtuoso Baumeister aria, often cut in both performances and recordings.

In February 1966 Wunderlich was in Berlin, recording both Beethoven’s Missa Solemnis and the choral parts of Haydn’s Die Schöpfung, both with the same team of soloists and with Herbert von Karajan conducting. The rest of Die Schöpfung was recorded in 1968 and ’69 – after Wunderlich’s death, and with Werner Krenn taking over the remaining tenor solos. Fortunately Wunderlich recorded Uriel’s most important solos, including a ravishing account of the aria ‘Mit Würd’ und Hoheit angetan’.

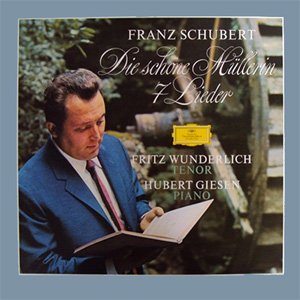

Two of the most important of Wunderlich’s DG recordings are the lieder issues, Schumann’s Dichterliebe and Schubert’s Die schöne Müllerin, the latter being Wunderlich’s second studio recording of the song cycle, made only two months before his death. This recording was one of my first LPs, a gift from a music teacher who had a duplicate to spare, and it was my favourite record for a long time. I was around 13 years of age, and I must have driven my parents crazy playing the same record over and over. Still today, when I play this recording on CD, I await the awful moment in the eighth song ‘Morgengruss’ where a series of loud clicks anticipated a repeated grove, continuing the words ‘blauen Morgen’ again and again until I got up and moved the pick-up.

Comparing Wunderlich’s two commercial recordings of Die Schöne Müllerin there is not only a development of the voice, but also a striking difference in the interpretations. In the early recording for Europäische Phonoklub Wunderlich is clearly a little afraid of the task. The youthful, fresh voice is in itself a pleasure to listen to, but as an interpretation the 1957 recording has far to go. Wunderlich is cautious, he is slightly out of tune in several songs, and he often breathes in awkward places, breaking a phrase into several smaller – and he is not helped much by the heavy and not very inspired accompaniment by Kurt Heinz Stolze.

When he recorded the cycle again almost ten years later he had had a tremendous experience as a lieder singer on stage, having sung Die schöne Müllerin countless times in public – mostly with Hubert Giesen, who is also his accompanist on the DG recording. Giesen gives solid support without bringing much magic to the accompaniment, but he is nevertheless an improvement from Stolze. As an example of the difference between the two versions listen to the sixth song – ‘Der Neugierige’. In the phrase ‘Ein Wörtchen um und um’ one can on the DG recording enjoy the superb cantilena that Wunderlich did not posses in 1957. The second recording is a landmark in lieder singing on record, with beautiful phrasing and secure breathing as just the foundation of a truly great interpretation. It is not a Fischer-Dieskauian psychologically complex reading, but simply a straightforward and sincerely musical performance. Wunderlich now gives much more meaning to the words without any loss of the freshness, and it is a delight to hear the cycle sung by a mature tenor in full command of the music.

When he recorded the cycle again almost ten years later he had had a tremendous experience as a lieder singer on stage, having sung Die schöne Müllerin countless times in public – mostly with Hubert Giesen, who is also his accompanist on the DG recording. Giesen gives solid support without bringing much magic to the accompaniment, but he is nevertheless an improvement from Stolze. As an example of the difference between the two versions listen to the sixth song – ‘Der Neugierige’. In the phrase ‘Ein Wörtchen um und um’ one can on the DG recording enjoy the superb cantilena that Wunderlich did not posses in 1957. The second recording is a landmark in lieder singing on record, with beautiful phrasing and secure breathing as just the foundation of a truly great interpretation. It is not a Fischer-Dieskauian psychologically complex reading, but simply a straightforward and sincerely musical performance. Wunderlich now gives much more meaning to the words without any loss of the freshness, and it is a delight to hear the cycle sung by a mature tenor in full command of the music.

By only singing lyrical parts until his mid-thirties, Wunderlich left himself the choice of his future repertory: From where he stood at the time of his death he could have gone in several directions. Wunderlich cleverly rejected all the tempting offers he received from Wieland Wagner, who wanted him to sing Lohengrin in Bayreuth as early as 1958. Wunderlich was firm: No Wagner until after his 40th year. It has often been stated that Wunderlich would have been a sensational Lohengrin, von Stolzing or Siegmund, or even Tristan. But perhaps he would have preferred to sing the Italian lirico spinto repertoire, with parts like Radamès in Aïda and Cavaradossi in Tosca – both certainly to have been within his grasp in just a few more years.

Listen for instance to the live-recordings of La Traviata and to the Verdi Requiem – here he sounds every bit as ‘Italian’ as most native Italians. Thanks to Herbert von Karajan, a strong advocate for singing operas in their original language, we can also hear a live recording from the Vienna State Opera of Wunderlich’s Don Ottavio in Don Giovanni in Italian. And what a difference from the studio recording of his two arias in German. Suddenly the music flows easily, and it is as if the Italian language presses a button in Wunderlich, almost transforming him to another singer, seemingly born in Milan or Rome. At the time of his tragic death he was planning to add both The Duke in Rigoletto and Rodolfo in La Bohème to his repertoire.

Wunderlich often sang the small but tricky part of the Italian singer in Der Rosenkavalier, and one of these performances has been preserved; a gala performance at the Munich Opera in May 1965. Here Wunderlich surpasses himself singing with an almost diabolical ringing force right through to the point where he is interrupted by Baron Ochs. This aria is well worth the price of the three CDs altogether!

Whether his voice would have coped with this treatment in the long run is of course purely speculation today, but the Finnish bass Kim Borg, who sang with Wunderlich on several occasions, recalls the way that Wunderlich always gave his most in every single performance: “Even though it sounds like the sort of thing one would only say looking back, I was already then suspicious that Wunderlich’s career would perhaps be a short one. He simply gave everything he had, he never spared his voice – and I think he would have had problems later if his career had been longer”.

Wunderlich never lived to experience problems like these. In September 1966 he was due for rehearsals at The Metropolitan in New York for his house debut as Don Ottavio in Don Giovanni. But the air ticket across the Atlantic had to be cancelled. The death notice in the newspapers read only one line: ‘Fate has taken everything from us’.

Hello Henrik,

stepped in for an indisposed Josef Traxel is not quite correct. Wunderlich had an engagement at the Stuttgart Opera, but didn’t get any performances. He became increasingly desperate and his colleagues decided to help him. To this end Traxel called in sick and the Opera Management sent for Windgassen who was also privy to that scheme and said sorry, no chance I’m completely hoarse, at the end they let him perform, well, and the rest is history.

A great story of collegial support among artists.

hydra – вход hydra, ссылка гидра

discover here Как зайти на гидру