The Danish bassbaritone Peter Schram made his operatic debut at the Royal Opera in Copenhagen in 1841, two years before Patti was even born, and he sang Leporello for the first time 1846. He was by then a regular soloist at the Royal Opera, but wanted to continue his studies in Paris. Garcia was enthusiastic about his Danish pupil, and he suggested Schram for the Paris Opera. But Schram was homesick, he declined and returned to Copenhagen. His only appearance outside Denmark was in Stockholm where he sang alongside Jenny Lind. After his retirement as a singer in 1889 he continued to perform as an actor until a few months before his death.

The fact that we today can hear the voice of a singer born in 1819 we owe to Gottfried Moses Ruben, himself born in 1837 into a Jewish family in Copenhagen. As a young man he was employed in his father’s gentlemen’s outfitting shop, and after living in London for eight years he married the daughter of a wealthy Copenhagen merchant in 1872 and now moved to Lisbon. His wife’s bad health forced them to return to Copenhagen after three years, and Ruben was now named Portuguese consul-general. He set up a business of importing wine and cork from Portugal, and this apparently was a lucrative business; his yearly income was now more than 8.000 kroner – in comparison a girl servant around 1890 received from 100 to 120 kroner a year.

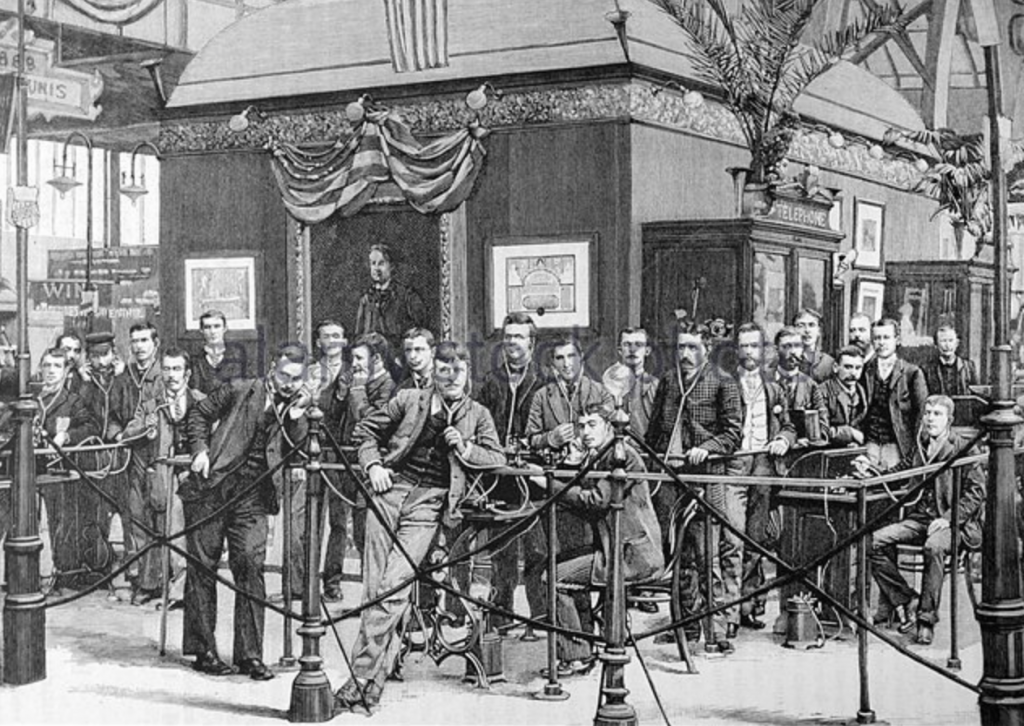

Precisely where and when Ruben first heard Edison’s perfected phonograph of 1888 we do not know, but it might well have been at the Paris exhibition during the summer of 1889, where Edison himself also was present, or it could have been in Germany or England. At any rate it was from London that he imported his first Edison phonograph – from Colonel Gouraud’s Edison Phonograph Company.

Ruben became Edison’s agent not only in Denmark, but in all the Nordic countries; Sweden, Norway and Finland (Iceland was at that time a part of Denmark). He teamed up with the firm Cornelius Knudsen, specialising in optical and mechanical devices, and one of the first companies in Europe to import one of Edison’s original tin-foil phonographs more than 10 years earlier. Ruben made Cornelius Knudsen sole retailer of Edison phonographs in Copenhagen, and in late September 1889 the first machine arrived – along with a technician from London.

All Summer the Danes had been reading about Edison’s new invention. In August the newspapers had enthused about Edison’s visit to London, and only two weeks earlier Edison had demonstrated the machine to the German Emperor. The Danish public was eager to experience the wonder for themselves, and Ruben knew just how to get the public even more interested; he offered a demonstration of his phonograph at the Danish court.

The first notice of Ruben’s new phonograph in the Copenhagen newspapers appeared in Dagens Nyheder on September 29th:

“An Edison phonograph has now arrived in Copenhagen. The machine, owned by a consortium, was yesterday sent to Fredensborg [Summer residence of the Royal family]….The invention received thundering applause from the royalty”.

“An Edison phonograph has now arrived in Copenhagen. The machine, owned by a consortium, was yesterday sent to Fredensborg [Summer residence of the Royal family]….The invention received thundering applause from the royalty”.

The royalty on this occasion was not only the Danish King Christian IX and Queen but also included czar Alexander of Russia and his Danish born czarina.

The official journal of the court gives us a glimpse of the demonstration: “The demonstration, given by consul-general Ruben and the head of the company Cornelius Knudsen, assisted by a technician employed by The Phonographic Company [sic] in London, took place in the Conservatory and began around 10 [P.M.]. His Majesty the King first received a greeting from the Danish colony in London, and it was apparently with equal amounts of surprise and joy that His Majesty this way was greeted with the warmest wishes of happiness and blessings for himself and his family. Later was heard several musical compositions, among them Wörishöffer March played by a large band…The performances went on for about two hours. The three gentlemen who demonstrated the phonograph were fed in a room in the eastern wing.”

The newspaper Politiken stated on October 1st that the Edison phonograph had been imported to Copenhagen by Ruben and Knudsen “some days ago”. They have already received numerous orders for machines, in part by businessmen here in town who wants its services, in part from estate owners around the country who wants it to amuse themselves and their guests. Consul-general Ruben has during the last couple of days received dozens of requests from aspiring agents for the speaking wonder.”

This was not all quite true. It actually took Ruben some time and effort to get just a few agents around Denmark – the fact that a machine had a retail price of 700 kroner was undoubtedly discouraging for anyone interested. But the notice in Politiken was nevertheless clever marketing by Ruben: The phonograph had triumphed even before the public had had a chance to hear it!

Ruben was fully aware of the power of the press in a venture like his, so he invited them to a special demonstration on October 3rd at 1 P.M. in his home apartment.

The Phonograph was an Edison “class M” model driven by an electric motor powered by two wet cells. The machine had six pairs of rubber hearing tubes, and the gentlemen of the press had to wait their turn to hear the wonders of the novelty. “First the apparatus brought out a salute to the press. Every word was clearly heard, every nuance in the voice, and even a faint involuntary cough was audible” wrote Berlingske Tidende.

Everybody in Copenhagen wanted to hear the phonograph, and a temporary showroom was rented. Anyone willing to pay 1 krone could put the rubber tubes to his ears and for himself experience the wonderful novelty.

Ruben now ordered 50 phonographs directly from the Edison Phonograph Works in West Orange, along with 1500 blank cylinders and “supplies for three months” as the invoice states – recorders, diaphragms, belts and other spare parts. All this was shipped in 36 cases and 10 barrels on board the S/S Island sailing from America to Denmark on November 2nd.

With their new equipment, The Danish Edison Phonograph Company, as Ruben and Knudsen named it, opened their new premises in Copenhagen on February 23rd, 1890. It was a large room on the first floor of a house near the Tivoli Gardens, and besides being used for demonstrating the phonograph to the public, the room was also used as a recording studio. It was equipped with both an upright and a grand piano, and over the grand piano a large recording horn was lowered. It was probably here that the main part of the Ruben collection were recorded. Recordings by well-known singers and actors were essential to attract an audience now that the phonograph was yesterday’s news, and Ruben constantly needed new artists and repertoire.

In July 1891 an interesting advertisement appeared in Politiken: “Other new items on the Edison phonograph:…P. Schram: The Leporello aria…”. The phonograph was now on display in the waxworks housed in the same building where Ruben had his private apartment, and it was here one could hear the recording by the baritone Peter Schram (1819-1895) who had retired from the Royal Danish Opera in 1889. The aria, “Notte e giorno” from Mozart’s Don Giovanni, is preserved in the Ruben collection, and this cylinder is in fact a world record: It contains the oldest singer (in terms of date of birth) that we can still hear today.

It is strange to listen to the voice of a man who was born at a time when Beethoven, Schubert, Rossini, Bellini and Donizetti were still active composers. Peter Schram made his operatic debut at the Royal Opera in Copenhagen in 1841, two years before Patti was even born, and he sang Leporello for the first time 1846. He was by then a regular soloist at the Royal Opera, but wanted to continue his studies in Paris. Garcia was enthusiastic about his Danish pupil, and he suggested Schram for the Paris Opera. But Schram was homesick, he declined and returned to Copenhagen. His only appearance outside Denmark was in Stockholm where he sang alongside Jenny Lind. After his retirement as a singer in 1889 he continued to perform as an actor until a few months before his death.

The Peter Schram cylinder contains not just the complete opening aria from Don Giovanni, but also the first verse of “Madamina! Il catalogo è questo”. Schram sings unaccompanied and with great rhythmical freedom. It is clearly a voice of an elderly baritone, and the style is not what we normally hear today. Schram sings in Danish, and he adds little embellishments to the music and even a cadenza to the fermata in the middle of the first aria. The style is very similar to the one Sir Charles Santley demonstrates in his recording of “Non più andrai” from Le Nozze di Figaro. No wonder, since both singers studied in Paris with Manuel Garcia, brother of Maria Malibran and son of the other Manuel Garcia, the famous creator of Rossini’s Almaviva in Il barbiere di Siviglia.

In theory the cylinder could well have been be recorded before July 1891, when it was first advertised, but Ruben had no way of duplicating a cylinder, and only a limited number of phonographs could record the same performance. In case of an especially popular recording the artist may have recorded the same piece many times over a period of time, and Schram could well have repeated the aria several times for Ruben. It could consequently have been recorded as late as June 1895. But it would still be the earliest recording of music by Mozart.

In the Ruben collection are recordings by several other Danish singers of importance; The baritone Cornelius Petersen, who later changed his name to Peter Cornelius and his voice to tenor, is represented by two songs. He later recorded extensively for both the phonograph and the gramophone, and sang both at Covent Garden and in Bayreuth.

All the cylinders in the Ruben collection are preserved and has been transferred by the State and University Library in Aarhus, Denmark. More here (in Danish).

Gottfried Ruben died following brain surgery in 1897, at the early age of sixty and was buried from the mosaic mortuary in Copenhagen. Among the many flowers that decorated the room was a wreath with a banner from the staff of the Edison Works.

Wow. This is extremely interesting. Thank you!!